Apologies for the delay inbetween posts. Over the past few days, I have been doing far more meaningful things, like reading about this

Capital Grille chef who stole customers' credit cards to fund his toy car hobby. WTF? How do you do something like cook steak (awesome, manly) but at the same time collect toy cars (creepy, childlike, possibly to bag kids)? Good thing he's out of work now; I've gone ahead and done everyone a favor by registering him

here. Hopefully he doesn't get hired at another Capital Grille where he might decorate my lobster mac and cheese with more than the four requisite cheeses.

Unrelated: in college, my first accounting professor had a peculiar middle-America accent that caused him to pronounce "depreciation" as "deprishiation." I don't have much meaningful to say about to him, but realized this is my only chance to mention how annoying that SOB was, since today's post is about depreciation.

First off, those of you that read about my

distaste for CPDS' may have also closely read

the keyboard shortcuts and noticed the SYD function on the bottom right-hand corner. SYD stands for "sum of the years' depreciation" (read more about it

here, because I don't feel like writing an accounting lesson) and is an alternative to the straight-line method that allows for a greater amount of depreciation in the early years of using an asset. If you had asked me what SYD is prior to a couple of weeks ago, I could have only told you about a guy I know from Queens, but now I can tell you it's an excel formula written as follows:

SYD(cost, salvage, life, period). Which goes to show how shitty my education from Professor Deprishiation was.

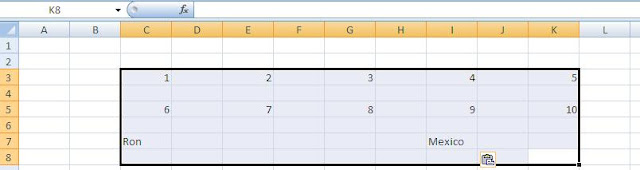

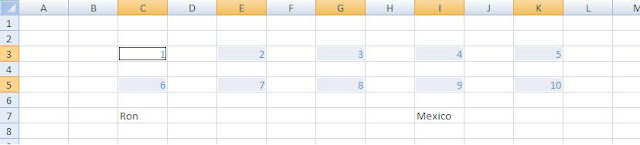

Stepping back (I bet you heard someone say this today) from SYD to depreciation more broadly, you have probably spent some time learning about how to build out depreciation for any new capital expenditures in a model. The most common method I have seen is the use of a "waterfall;" assuming you project five years in your model, there would be one line showing annual depreciation for the first year of capex, another line for the second year, and so forth. So let's look at a simple straight-line case:

For every year (or period) of capital expenditures, you add another row to show the depreciation amounts in each ensuing year. In the above example, these rows are totaled in row 21 to show the total depreciation amount (for new capital expenditures, only). It's quite the bitch to update the depreciation waterfall anytime you change an assumption on timing (like 5 years to 4 years) or add another year into the projections (thus requiring another row to be manually inserted). Even if you have automated your formulae to adjust for timing assumptions (as rows 14-19 in this spreadsheet are), you cannot avoid adding another row if you are extending these projections out to 2015.

The solution is to write a formula in one line that accounts for all of these assumptions dynamically; in other words, have a depreciation waterfall built up in one row of a spreadsheet. Here's how (based on the example above):

- Use rows 9-12 as assumptions

- In cell G23, enter the formula =+SUMPRODUCT($G$10:$M$10,1/$G$11:$M$11,IF($G$6:$M$6<=G$6,IF($G$12:$M$12>G$6,1,0),0)) followed by ALT + SHIFT + ENTER

- Drag the formula in G23 to L23

- Don't forget to enter in a number (any number is fine) in cell M11 to avoid dividing by zero in your calculation

The above method is obviously an array formula, where calculations are done using corresponding cell ranges of equal size; so the SUMPRODUCT function is really operating as G10 x (1/G11) x a + ... + M10 x (1/M11) x a, where "a" is an operator that determines whether each depreciation amount should be counted for the current time period (the current column).

The logic for "a" is based on the year of the given capital expenditure and its last year of depreciation. So, if G10 x (1/G11) is based on a capital expenditure from year 1 (column G) that depreciates through year 5 (column L), then "a" will equal the number 1 in each of those years. Otherwise, "a" will be 0, which multiplies against the depreciation amount to make it zero, thus excluding it from the depreciation total. A good example of how this calculation works can be found in K14 through K19. If K14 belongs, our SUMPRODUCT formula multiplies it by 1, and if not, then by 0. Thus the SUMPRODUCT formula is doing the work of the SUM formula in row 21, in addition to the calculations for the depreciation waterfall directly above.

Thus, you now have the ability to insert another year in your model, and allow for

depreciation to be calculated precisely in one line, based on the assumptions you enter and without the need for manual adjustments.

So why have I not told you anything about sum of the years' depreciation, even though it's just calculated in the same waterfall format with different numbers for different years? To be honest, it's complicated as shit to write a dynamic formula into one line. So here it is for cell G23:

=+SUM(IF($G$6:$M$6<=G$6,IF($G$12:$M$12>G$6,SYD($G$10:$M$10,0,$G$11:$M$11,IF($G$9:$M$9+IF($G$9:$M$9>F$9,-1*F$9,RANK($G$9:$M$9,$G$9:$M$9,0)-RANK(G$9,$G$9:$M$9,0)+1-$G$9:$M$9)<=$G$11:$M$11,$G$9:$M$9+IF($G$9:$M$9>F$9,-1*F$9,RANK($G$9:$M$9,$G$9:$M$9,0)-RANK(G$9,$G$9:$M$9,0)+1-$G$9:$M$9),1)),0)),0)

I'll explain it some day when I feel like it.

-F-One